What can you say about a man named Weiner who’s famous for exposing his penis to the world? All the jokes have been made, but this film is no joke. It’s a real close up, unadorned look at the man behind the appendage, with the caveat that I and you as watchers are all part of his need for exposure.

WEINER– with its ridiculously perfect title–trains an unwavering lens on former U.S. Representative Anthony Weiner and his failed 2013 run for mayor of New York. It’s a stunner. Not only does the film offer intimate access to Weiner at home and on the campaign trail, but also offers a front row seat to the explosion of a scandal, the dissipation of a marriage, and the sensationalism of political coverage in a social media-saturated, entertainment-obsessed culture.

WEINER directed by Josh Kriegman and Elyse Steinberg, won the Grand Jury Prize for best documentary at Sundance and welcomes us behind the scenes of a campaign that thought it was rising from the ashes, only to implode from within at the hands of … an arrogant narcissist? An unlucky guy with a sexual tic he can’t control? We never really find out. But I watched twice to see if I could, and each time it was like watching the same car wreck in slow motion, pre-ordained by the gods; I could barely believe what I was seeing.

The film begins silently in black and white with the following hilariously profound quote from Marshall McLuhan: “The name of a man is a numbing blow from which he never recovers.” Then we hear Weiner’s first words: “Shit. This is the worst. Doing a documentary on my scandal … The punchline is true about me. I did the dumb thing. But I also did a lot of other things too.”

You will recall that the congressman, a liberal attack dog for doing the right thing had scored popular points for arguing for medical care for 9/11 workers because “It’s the decent thing to do.” But after it surfaced that Weiner had texted images of his genitalia not just to a select few women, but accidentally to his thousands of online followers, he resigned in disgrace. Two years later– after rehab, a new baby, and a spread in People Magazine with his wife Huma Abedin (Hillary Clinton’s right hand advisor), in which he proclaimed himself to be a new person– he decided to put his refurbished image to the test and in 2013 run for mayor of New York City.

What happened next shocked everyone including the filmmakers who thought they were documenting the second coming and instead found themselves in free fall along with everyone else (wife Huma, the entire campaign team, and the world) and discovered that Weiner, unbelievably, had done it again. And this time he had another pip of a moniker “Carlos Danger,” his online alter ego for whom “danger” clearly involved not just displaying photos of his nether regions to selected recipients, but tempting his political fate.

The cameras follow him behind closed doors as he and his aides scramble to manage what to say and how to say it. The camera is there on the trail as Weiner, having shoved his junk in our faces again, keeps trying to steer the conversation back to housing in the Bronx. The camera is there at home with his beautiful beleaguered wife Huma, shellshocked and embarrassed, caught between her loyalty to her husband, their marriage, and his future, and her political marriage and friendship with Hillary Clinton and its impact on Clinton’s imminent run for the Presidency. The awkward silences are deafening, Huma’s meekness in the face of his arrogance is baffling.

At first I was frustrated by the film’s lack of a point of view– I wanted someone to ask “WHY.” When a well–spoken earnest man at a tense campaign stop asks why the voters should trust him again after he has asked for and been given a second chance, Weiner lambastes the man for even asking, and accuses him of “denying others the right to make up their own minds.” His bravado actually elicits scattered applause, and there we see some method in Weiner’s madness. Weiner engages in behavior that dares folks to judge him, then blames them when they do, deflecting attention from the question which is, “Who are you and why should we trust you?” Weiner and the film continually challenge us to walk the line between what’s public, what’s private, and what we do and don’t have a right to know about our public servants in the context of a voyeuristic global culture where just about everything can be known about everyone.

Weiner continually provokes and reframes every encounter so as not to be accountable. He seems to goad so he can fight back. He blames people for overstepping their boundaries after he’s blurred them. The person who comes closest to framing the “Why” question is MSNBC’s Lawrence O’Donnell who high-handedly asks, “What is wrong with you?” But it’s Weiner who has the last word. In an incendiary on-air exchange Weiner turns the tables, swivels his chair, and whips himself into a smirking frenzy claiming the moral high ground, chastising O’Donnell for being self-righteous. He even brags he should be on more often with O’Donnell so “maybe I’ll kick your ass every night.” Later he re-watches the exchange on TV and says it makes him feel better, more powerful, stronger.

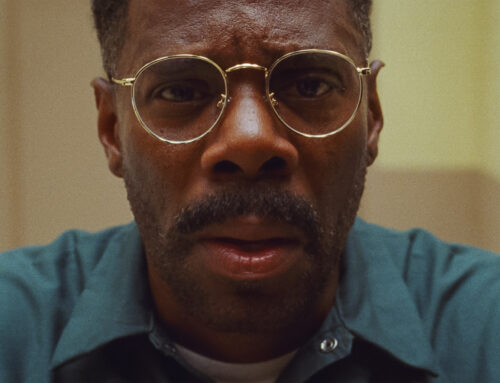

Ultimately the film’s decision to back off, suspend judgement, and get out of the way so we can see Weiner for ourselves is the right one. There is plenty to see. What we see is a guy who uses his considerable intellect and volatile personality to first provoke, then verbally parry any perceived attack. We see a guy who, caught with his pants down, continues to talk down to his wife. We see his body language, a guy leaning back, legs spread, hands clasped behind his head, thrusting his crotch forward in shot after shot, even as he’s attempting to conduct a sensitive group talk in his living room with his wounded campaign staff in the immediate aftermath of the scandal. Mightn’t we have expected a more contrite, less cocky and languorous posture?

A parting shot seems to be a surprise to Weiner himself; he flashes the finger while fleeing the press corps he has prodded, courted, and condescends to. It’s all over the news. “I can’t believe I gave the press the finger” he sighs. But is he really upset? Or is he just turned on? Near the end of the film, the filmmaker does ask Weiner a pointed question: Why has he let them film this?

As you watch the movie and see Weiner squirm and sweat, rant and rave, bicker and never back down– keep the question in mind and see if you don’t get off on the intensity. I’m pretty sure Weiner does.

[…] https://joyceschoices.com/movies/movie-weiner […]