What’s most extraordinary about KILLERS OF THE FLOWER MOON is not that it was made by the masterful Martin Scorsese who began bringing it into focus pre-pandemic. Nor that it features one of Leonardo DiCaprio’s most subtly communicative performances in a career of compelling, wildly varied, and complex roles. Or that it delivers a central transfixing performance by the sublime Lily Gladstone. No, the most powerful thing about this film is the story itself, that it has been hidden from history, unknown in most circles except that of the Osage Nation who lived it. In Scorsese’s latest, we experience the shock of a saga so baldly heinous it is hard to imagine it had almost been erased from history.

Based on the 2017 bestseller by David Grann, KILLERS OF THE FLOWER MOON: THE OSAGE MURDERS AND THE BIRTH OF THE FBI reveals a hidden tale of mass murder committed during the 1920’s in Osage Nation (Oklahoma) about 30 years after the Osage discovered rich reserves of oil on land to which they had been relegated because it was thought to be worthless. The black gold discovered there brought great wealth to the Osage, but also a rush of white men whose jealousy and greed unleashed a Reign of Terror. We learn early on that the Osage, while wealthy, were legally deemed “incompetent” to manage their newfound wealth and were required to have white guardians oversee how they spent their money, which could only be passed down through their bloodline. It didn’t take long for white men to start taking Osage wives and having children, thus allowing them to inherit. Soon more and more Osage were turning up dead, their deaths ascribed to everything from suicide to strange sicknesses.

Grann’s book focused on the FBI’s investigation under J.Edgar Hoover, the solving of the murders, and their subsequent trials, but there is nothing of the thrill of a true crime drama in Scorsese’s film. In fact, the script lets us know at the outset that this is not a “Who done it,” but rather– as the director himself said at a press conference in Cannes–“Who DIDN’T do it?” Indeed, early in the film, Scorsese embeds exposition of these “mysterious deaths” in wordless but revelatory scenes underscored by his longtime musical collaborator the late Robbie Robertson.

So what’s left to drive this story forward? Given that we know so much at the beginning, I felt little initial narrative pull. But Scorsese who also co-wrote the screenplay with Eric Roth had something darker in mind. At the expense of some dramatic tension, he chose to deliver a penetrating meditation on individual and collective corruption. We are asked to examine a genocide unfolding in slow motion and in close up on the characters who lived it. Scorsese’s directorial skill and conviction, the hushed intensity of these performances, and the audacity of the crimes committed, slowly but surely absorbed my attention and held me there for 3 hours and 36 minutes. The film continues to work on me still.

The film’s opening sequence re-centers the narrative on the Osage as they bury a ceremonial pipe in the ground–along with their way of life–just ahead of the gusher which will lure their oppressors to their land. The sequence is metaphorically potent as the tribe dances in the setting sun, oil raining down on them like blood. The movie then zeros in on the relationship between Mollie, a wealthy Osage woman, and Ernest. Mollie is played by an incandescent Lily Gladstone who was raised on the Blackfeet reservation in Montana and learned Osage along with her co-stars for the role. In a cast of global superstars, she is easily the most magnetic person onscreen. The serenity of her elegant face masks a well of emotion; her dignity is the moral center of the film.

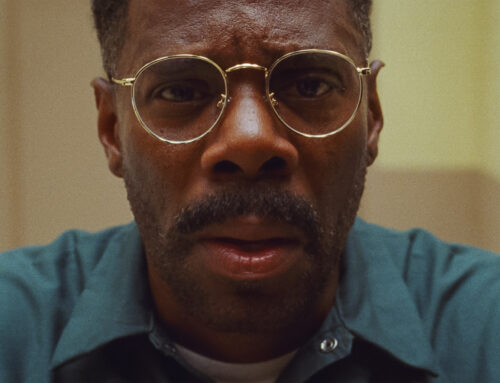

Mollie gives little away–except her whole heart to one Ernest Burkhart, the white man who offers to chauffeur Mollie around town. Why she falls for him and what he represents to her is a bit of a mystery, though she finds him handsome. To my eye, this is the least attractive Leonardo DiCaprio we’ve ever seen onscreen. His Ernest has a jowly underbite of misshapen teeth, and may not be true to his first name. DiCaprio is convincing as a weak man, dangerous because he doesn’t know himself and is led around by those more powerful than he, namely his big shot uncle William Hale, a wealthy rancher. Hale has endeared himself to the Osage, speaks their language, and lets everyone, including his nephew, call him “King.” Robert DeNiro’s Hale is a sinister amalgam of affability and arrogance as he casually lays out the rationale for his greed, and one by one all of Mollie’s sisters die. The FBI enters the story in the last hour in the person of Jesse Plemons as Tom White in a 10-gallon hat and an unrelenting gaze. He sees what there is to see and there is no doubt he will get his man. But there’s little relief in it; it’s too little, too late.

At its core, the movie is a tale of love, trust, and betrayal intertwined in one family, which is a template for a larger more insidious story buried in that intimate human tragedy. How much did Ernest know? How much do we let ourselves know about our own history? How can such evil exist in such ordinary men? The film supplies no easy answers, but makes the questions inescapable. Killers of the Flower Moon is not perfect, but it will stun you with the depth of its moral certitude. In this deeply personal work, Martin Scorsese takes an unflinching look at our complicity in the ravages of white supremacy, and brings us face to face with the tainted history of the American origin story and the evil embedded with what’s good in the ambitious American character.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.