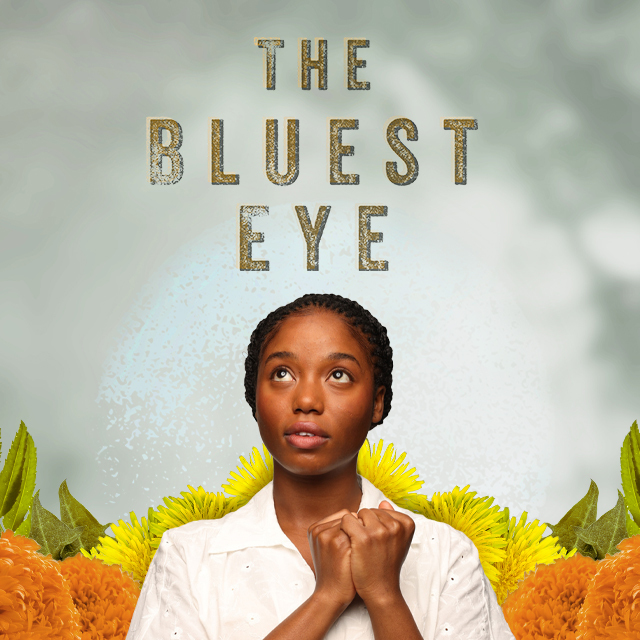

The title alone–THE BLUEST EYE–suggests the shards of an iris, a lens on a deep dark sea of meaning. Now, the depth and richness of the Nobel Prize-winning author Toni Morrison’s language and vision is profoundly illuminated by Lydia R. Diamond’s sleek 2005 adaptation of Morrison’s first novel and The Huntington’s graceful and penetrating production– a sorrowful sweep of broken lives and shattered psyches. Awoye Timpo’s direction allows the audience in on two sides — the actors in between– as we witness the tale and ourselves as we see it. What we see is painful, ugly, and clear — if we can bear to look.

Once upon a time in 1941, Ohio, there lived a girl on the cusp of womanhood named Pecola Breedlove. She was poor, Black, and ugly– or so she thought and not by chance. Everywhere she looked showed her to be far from the “fairest” of all: movie stars like Jean Harlow and Shirley Temple, the standard blonde-haired, blue-eyed dolls, the white store clerk who refused to look at her or even touch her hand to take her hard-won pennies in exchange for a Mary Jane candy dropped on the counter. Her only recourse? The demented soothsayer Soaphead Church (Brian D. Coats) who might grant her desperate wish to have the bluest eyes– THEN she would be beautiful and loved!

This is a familiar story to any little girl who wishes to be beautiful and loved, but the desire and its consequences are grossly distorted for an African American child in a dominant white culture that says Black people are not just ugly — they are nothing. It doesn’t stop there. Once absorbed, the hurt twists in on itself and into profound self-loathing as well as externalized rage, violence, and dysfunction. What this production makes horrifyingly clear but manages to convey so compassionately, is that those who are hurt–hurt themselves and those around them, and this generational disfigurement is cruelly self-perpetuating across race and time.

And so the production unfolds in a mournful tapestry of abundant suffering and threadbare solace. At its center is Pecola Breedlove tenderly played by Hadar Busia-Singleton with her lovely, wide eyes uplifted. She is innocence personified, reciting from her Dick and Jane primer –priming her for disappointment in her own cold, violent, and fractured family. Her lonely, limping mother Mrs. Breedlove (McKenzie Frye) delivers an outrageous tale of childbirth in which her pain was minimized by white hospital staff as “not much,” like that of “an animal”; Frye blesses us with her aching vocals throughout.

And there is a pivotal scene which will never leave my mind’s eye involving Pecola’s embittered alcoholic father Cholly (Greg Alverez Reid), an incident of sexual humiliation in the flower of his youth at the hands of white men holding flashlights; the unbearable cruelty leaves scars of rage and shame that deform his relationships with women including his daughter. This scene shadowed in black and white is relieved by its lighting (Adam Honore), shafts of redemptive luminosity which allow us to see and understand without recoiling.

There are seeds of hope among these thorny roots. The scenic design (Jason Ardizzone-West) is remarkable in its aptness and simplicity. The action is set on what might be the cross section of a tree: a circle of branches hangs above a pair of concentric wooden stumps below, a platform on which branches of backstories in a family tree are told in the round; slices of a painful legacy– might that legacy be healed in the telling? The actors circle time and space, sometimes singing a cappella hymns of lamentation and faith, at others, lighter tales of Pecola’s sweet and funny girlfriends Frieda (Alexandria King in a dual role as Cholly’s early love Darlene) and Claudia (Brittany-Laurelle and also the Narrator?) hilarious in her defiance as she furiously dismembers her blonde, blue-eyed dollies. But then she had a loving Mama (Ramona Lisa Alexander) suggesting that her “self” is intact where love has taken root. These two little girls will later try to save an impregnated Pecola by literally planting seeds of marigolds in a soil that might bear fruit.

Diamond’s play illustrates with such potency and grace, the clear-eyed representation of the insidiousness, the havoc, hatred, spiritual, psychic, emotional and physical ruin racism wreaks on a single soul and a race of people. The ultimate disintegration of Pecola Breedlove–her fragmented self, in a daze, staring into a mirror in which she cannot see who she is– but only her now completely distorted self peering back at her with her oppressor’s blue eyes. We are left to feel compassion and remorse.

These disturbing truths could make some folks mighty uncomfortable– but what are artists for? The show lands at a critical time– Morrison’s book has once again been banned, this time in Missouri’s Wenzville school district as of January 2022 while the hotly debated “Critical Race Theory” demands that we see our history whole. The Huntington Theatre Company’s production of THE BLUEST EYE gleams like a prism refracting the shadowy truth, shedding more light the deeper we look.

SEE IT:

- IN PERSON Now through March 26 at the BCA’s Calderwood Pavilion,

- DIGITAL ACCESS February 14 through April 9, 2022.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.