After combing through the listings of franchise-fatigued superheroes now clogging big screens everywhere, I’ve come up with a list of well-made, challenging, and engrossing films for folks as sick of vacuous action adventure as I am. Over the next few days I’ll write about the following films that left me reeling: BABY DRIVER, THE BIG SICK, DUNKIRK, A GHOST STORY, LADY MACBETH, and the most recent I’ve seen, the scalding DETROIT.

I was not familiar with the historical events on which this film is based, a case of police brutality that unfolded during the Detroit riots of 1967. What I did know was that I was going to be in the hands of an exceptional filmmaker Kathryn Bigelow and screenwriter Mark Boal, the duo behind THE HURT LOCKER and ZERO DARK THIRTY. They had proven themselves fully in command of the rugged tropes of war: blood and guts, tension and fear, man’s inhumanity to man. DETROIT is darker than either of these accomplished films; it cut a hole in my heart and re-triggered my outrage and frustration over the unrelenting racial tension in these United States.

DETROIT works from the outside in, to the heart of darkness. The first scenes are, literally, a graphic shorthand of black history in America leading up to the migration to find work in northern industrial cities. Exactly 50 years ago on the date of this film’s release, the predominantly white Detroit police force raided a party on 12th Street celebrating the return of two African American GI’s from Viet Nam. Anthony Mackie as one of the servicemen radiates dignity in an impossible situation. The lack of a liquor license prompted the arrest of all 80-plus attendees; the arrests triggered looting and rioting, which in turn triggered the army and national guard to come to the aid of local and state police with tanks and machine guns.

Bigelow’s fluid camera is everywhere, capturing the tense, restless energy uncoiling over hours and days leading to a city on fire. Carefully interspersed newsreel footage and photos capture the rebellion outside while Michigan Governor George Romney (Mitt’s father) is shown on TV quaintly denouncing the “hoodlumism” overrunning the city. Hindsight is embarrassing; the extent to which white America underestimated the depth of racial hatred within its ranks is painful.

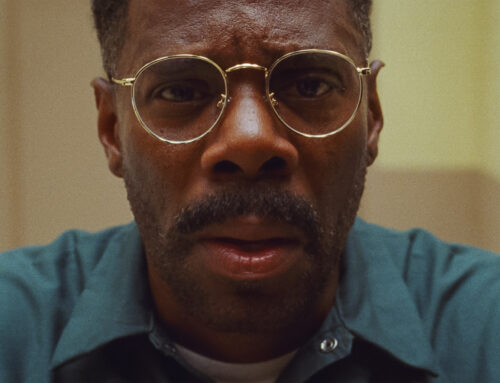

Bigelow guides Mark Boal’s script as it slowly zeros in on the people who will take center stage, carving out the arcs of their stories against the chaos. There’s Larry Reed, the sweet-voiced lead singer of “The Dramatics” (Algee Smith in an achingly vulnerable performance) who were pre-empted from performing that night. Not far away, Melvin Dismukes a black private security guard played by John Boyega (STAR WARS: THE FORCE AWAKENS) attempts to keep the peace, his turf, his life. Across town a bigoted white cop named Krauss fearlessly played by Will Poulter as unnervingly blind, cruel, and wily, has already been reprimanded for shooting a looter in the back earlier that evening; it’s a preamble to the events he’s about to set in motion.

On July 25, 1967, police and the national guard descended on the Algiers Motel where people had taken refuge. In search of a sniper (a reckless partier shooting out the window with a starter pistol), the police rounded up 12 people and proceeded over the course of a long, excruciating night to interrogate, torture, and eventually murder 3 unarmed black teenagers among 10 black men detained, along with two white women. The officers accused of the murders were eventually acquitted.

The film is agonizing but essential viewing. We can’t–nor should we–avert our eyes from what the victims lived through. The events are reconstructed from eyewitness testimony and court records. The film in turn, stands witness to the worst human instincts, and these actors fully commit. As the evening wears on, we experience every twist and turn of all psyches present: the racist cops fueled by fear who sate their anger and hate, as well as those young men and women at their mercy, clinging to their humanity, calibrating every breath in order to survive– but at what cost?

Boal’s script fashions a scene that is a microcosm of the plight of the powerless under the thumb of the dominant culture. It’s an eye-opening mini “movie within a movie” in which a black character “acts out” for the amusement of the partiers what can happen when a bigoted white man has you at the end of a gun and no matter what you say, you make it worse. Later in the film the ultra-rational Dismukes who has tried his damnedest to stay alive and hang onto his moral center, suddenly finds himself staring into the abyss. It’s suffocating, and infuriating.

But is it hopeless? Does a film like DETROIT help or hurt? Does turning these real life events into a “narrative thriller” cheapen the truth despite the sophistication of the filmmaking or because of it? Can anybody white say anything meaningful about anybody black? L.A.-based film critic Tim Cogshell writing for ALT FILM GUIDE says:

“…Detroit the Movie, is a dramatic thriller meant first to entertain – which it does and which is why I don’t like it and would never send anyone to see it, no matter how well intentioned and well made….a recently produced hometown documentary account of the events, 12th and Clairmount ….captures this history without degrading the victims through the adept use of the tools of narrative cinema to render us small. Unlike Detroit, it does not use good intentions and excellent filmmaking to once again, stylishly, beat down black people in a movie meant to make white people feel better about themselves. ”

I say– see it and talk about it. Then let’s talk about it some more.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.