At the end of 2020, a flood of movies was released all at once and it’s time to catch up with the best. Among them, is a film based on Tony Award-winning playwright August Wilson’s “Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom” starring Oscar-winner Viola Davis and the late Chadwick Boseman in his final film performance which might very well earn him a posthumous Oscar nomination. The Boston Society of Film Critics voted the entire stellar cast BEST ENSEMBLE.

Here to review the latest cinematic incarnation of Wilson’s work is guest critic Jacquinn Sinclair whose review of “Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom” first appeared online at WBUR’s The ARTery.

It’s clear within the first few minutes of “Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom” that two alphas are jockeying for the spotlight: Viola Davis’ Rainey and the late Chadwick Boseman’s Levee, a cornet player in her band. The film quickly takes viewers from a tent show in Barnesville, Georgia to The Grand in Chicago where Rainey and her band are performing. As soon as there’s a pause, Levee, looking for his turn in the sun, steps into the spotlight, sparking the legendary blues singer’s anger.

In the Netflix adaptation of Pulitzer Prize-winner August Wilson’s play by Ruben Santiago-Hudson, a Wilson regular onstage as actor and director, Rainey and her band head to Chicago for a one-day studio recording session. The simmering conflict between Rainey and Levee, the beauty and stress of being Black, and a love of the blues anchor the crackling narrative (available Dec. 18).

On the day of the recording in 1927, Rainey’s late to the studio much to the chagrin of her white manager, Irvin (Jeremy Shamos). Most of the band members show up on time except for Levee who was tardy because he was buying new shoes. While they wait for Rainey to arrive, the band sips on some “good Chicago bourbon” from Toledo’s (Glynn Turman) flask and talks trash about life, music and women, in typical Wilson style. Cutler (Colman Domingo) tries to lead the rehearsal, but Levee isn’t feeling it. Especially if the band isn’t going to rehearse his version of “Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom.”

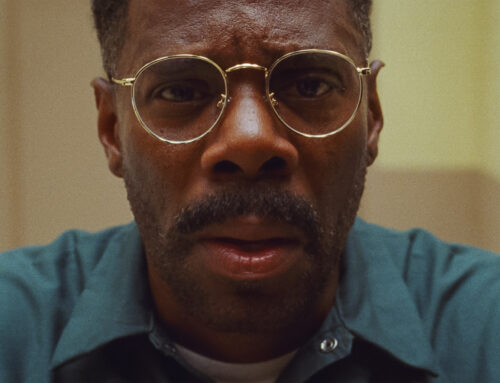

Much of the film’s majesty comes from George C. Wolfe’s direction and Denzel Washington and Todd Black’s production. Washington and Davis set screens ablaze in their performance of Wilson’s “Fences.” Here, Davis and Boseman both give riveting performances. Boseman’s character, marked by trauma, is furious with God and has allowed darkness to take up residence. In a tight close-up shot, Boseman’s eyes glisten and later fill with tears as he shares that his mother was attacked by a group of white men who took hold of her “like a mule” and had their way with her. Levee was young, but he tried to help his mother who pleaded with God to save her and ended up with a large scar across his chest and a deep, dark hole in his heart that threatens to swallow him up. Levee doesn’t think much of life, but death, he says, “got some style.” His roiling rage explodes as he screams up at the sky, challenging God. Boseman’s powerful performance underlines the tragedy of his early death.

(Foreground) Chadwick Boseman as Levee, (l. to r.)Glynn Turman as Toldeo, Michael Potts as Slow Drag, Colman Domingo as Cutler (Courtesy David Lee / Netflix)

The play takes a brief look into these people’s lives and tells a story of not just racism, fear and pain, but the courage it takes to persist, to thrive even in such precarious times. Newspaper headlines from the Chicago Defender, black and white stills and moments shared between the characters illuminate their complicated lives. There’s an ever-present undercurrent of danger; a tightrope that they must carefully navigate.

But this being a Wilson play, there are instances of love and joy too. Rainey snuggles up to her girlfriend Dussie Mae (Taylour Paige) and sings in her ear, the band shares laughs in the rehearsal room, Rainey encourages and celebrates her nephew, and Rainey and Cutler rest in their friendship for a beat over a conversation about the blues.

“White folks don’t understand about the blues, they hear it come out, but they don’t know how it got there. They don’t understand that that’s life’s way of talking.”

She talks of blues like a companion that stays with you: “This be an empty world without the blues,” she says while shaking her head slowly in reverence to what she’s given her life to. There’s not much backstory about Rainey and Cutler in the play, but the stellar actors convey years of history and camaraderie. She trusts him and he respects her that’s more than either of them can get in the outside world.

It’s one of the few, if not only times, Rainey, “The Mother of Blues,” seems to be able to relax and just be. A feat for a Black woman, especially during those turbulent times. The Academy Award-winning Davis takes up the entire screen when she enters a scene. She portrays Rainey, a big, Black, talented woman as defiantly proud. She follows her own rules and isn’t afraid to push back. She’s fully aware that her talent gives her some leverage, and until her voice gets “trapped in those fancy boxes,” on record, she will demand to be dealt with a certain way. She is constantly fighting. Not for the sake of being combative, but to be treated with decency. She asks for her stuttering nephew to do a little intro on a song and the band and her management discourage her, she wants to perform her songs the way she likes them, and she’s pushed (unsuccessfully) to go in another direction, she asks for a Coca-Cola before the start of the session, and it doesn’t happen. To make a point, she won’t start recording until she gets one and she makes a show out of slurping it down in a few loud gulps. Then, Davis — who reportedly used her own voice that was augmented by another singer — was ready to record.

By the film’s end, there’s one more stand Rainey takes, and another that she attempts to. First, she argues with management about paying her nephew and wins. But once that’s settled it’s time to sign some release forms. She hesitates and asks for them to be sent to her house, but Irvin insists that she deal with it now. Tired, she finally relents and signs the forms before driving off. I wonder if she released more than she realized. And Levee, upset that Sturdyvant won’t let him record the songs he wrote, finally finds a way to expel his fury.

That fury symbolizes all the frustration and anger that Wilson packs into a play that also highlights his lifelong love of blues and jazz. I wish I knew more about Rainey’s personal story, but this snapshot in time and this compelling adaptation are a terrific summation of why the late playwright was such an important figure in writing about the Black experience in America.

“Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom” is available to stream on Netflix.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.