“I heard you paint houses.” It’s an ominous line uttered in the first hour of the film, and the title of Charles Brandt’s best-selling biography of the “housepainter” who may have killed Jimmy Hoffa, on which the film is based. My father actually did paint houses, and died of a heart attack while doing so. In Martin Scorsese’s somber 3 1/2 hour magnum opus THE IRISHMAN, the euphemistic profession also carries the literal weight of mortality.

But the film is much more than the tale of a hitman who purportedly committed the crime. It’s an unexpectedly gripping elegy on a procession of tough guys and the meaning of their deeds, especially as embodied here by the Mount Rushmore of actors whom we’ve watched grow old over time in such parts on film. The movie is a meditation on patriarchs, politicians, killers, criminals, and working men, their legacies of blood and family, unions and loyalties, power and class, wrapped around a road trip to a requiem and one filmmaker’s ongoing examination of the meaning and meaninglessness of it all.

The Irishman (Robert De Niro) is Frank Sheeran, a WWII vet whose war wounds have primed him for a life of civilian criminality. Steven Zaillian’s screenplay is structured as a flashback within a flashback, CGI aging De Niro and his costars backwards as time recedes. We meet Frank at the beginning of the film and at end of his days in a Catholic nursing home. Wheelchair-bound, he recollects a road trip to a wedding years before when he happened upon the very gas station where his truck had broken down years before that, and his life took a fateful turn.

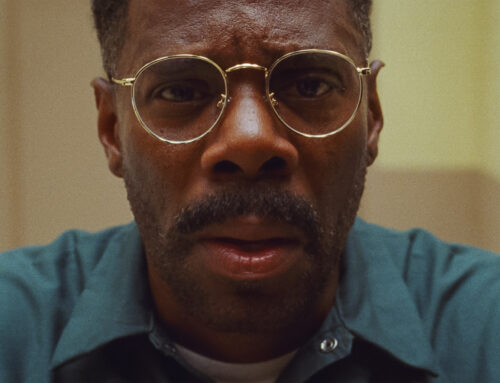

A cold, blue-eyed, mesmerizing Robert De Niro plays Frank Sheeran, a possibly decent man hollowed- out, muted, and wary, following his instincts up through the ranks of murderous characters. After a chance meeting with one Russell Bufalino (Joey Pesci) a snappily-dressed stranger at the aforementioned gas station, Frank is on guard as Russell checks under the hood and sizes up Frank’s engine problem. Months later, they meet again, but this time Russ sizes Frank up, and they end up going the distance together. Trucks figure this time too, as Frank eventually becomes Teamsters Union Boss Jimmy Hoffa’s strong man, confidant, and a high ranking union official himself. Al Pacino as the colorful, flat-topped Hoffa tempers Hoffa’s swagger and drive, with a great deal of personal charisma, and suggests Hoffa’s genuine belief in something larger than himself. It’s one of Pacino’s best performances.

The plot is both beside the point, and thoroughly engrossing. It’s a compelling orchestration of the various forces of the day– the mob, the union, the politicians — and how their toxic commingling culminated in Hoffa’s disappearance, JFK’s assassination, and assorted notorious mob hits. There are copious nods to Coppola’s seminal “The Godfather” which has forever embedded certain Roman Catholic rituals in our collective cinematic consciousness. These rituals tying people to their goodness: baptisms, weddings, family dinners, are served up right alongside restaurant shootouts, the discerning selection and disposal of lethal weapons, and one crazy, climactic riff on something “fishy” that made me remember poor Luca Brasi.

The film is lit more sepia than gold, the air thick with smoke and secrets, as long tracking shots draw us into an underworld of shady men enthroned in beat-up red leather banquettes. These are not Coppola’s warmly glamorous princes of darkness, but seedier, enervated creatures whose underbellies and expiration dates are showing. An ancient Harvey Keitel as big boss Angelo Bruno barely breathes as he talks in low tones, his giant pinky ring saying it all. Joe Pesci’s Russell Bufalino seldom changes expression, his eyes like black holes echoing something missing inside. In this company, Ray Romano as a Bufalino cousin and family lawyer, and Bobby Cannavale as yet another colorfully nicknamed thug “Felix ‘Skinny Razor’ DiTullio” register in a more vivid key, but already appear fraying around the edges of this rough life.

The women are either shrill, hard, or meekly invisible, their children inconsequential with the exception of one, Frank’s daughter Peggy (an affecting Lucy Gallina as a child/a daunting Anna Paquin as an adult) who hates her father’s world, a daughter Frank can’t reach, nor can Russell whose false attentions she bravely shuns. We come to see these characters through her eyes and it’s that view which finally haunts us.

If you were looking for blood and guts, Scorsese’s “The Irishman” has that, and more; it requires us to witness not just the raw, violent parts of our natures, but the soul-crushing toll that can take. How will these men feel at the end of their lives, how will they be remembered, if they are remembered at all? Like Clint Eastwood’s “Unforgiven,” “The Irishman” takes the gloss off these criminal potentates, and as played by an ensemble of actors whom we’ve watched grow old onscreen in such parts, the effect is bitter and poignant. In the film’s closing moments as we pull away, we are left with a glimpse back through a crack in the door before it closes on a life, alone, in the void.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.