Take one of the most flagrant miscarriages of justice in American history, fueled by racial hatred, hitch it to a minstrel show and you’ve got “The Scottsboro Boys.” Even more painfully relevant now than when it opened on Broadway in 2010, the Tony-nominated musical is having its New England premiere at SpeakEasy Stage Company in a production that was just extended through Nov. 26 — and what a full-throated, soulful and bitterly effective production it is.

The true story on which it’s based is enraging. On March 25, 1931 nine African American teenage boys (one of them was 12 years old) were strangers on a train in Alabama when they became linked by a single tragedy: They were falsely accused of raping two white women. All but one were initially found guilty and sentenced to death. After years and years of appeals, including a Supreme Court decision (Powell v. Alabama) that set precedent regarding racial representation on juries, all were permanently scarred from the fallout of a crime they did not commit.

John Kander and Fred Ebb, the sardonic duo who gave us “Chicago” and “Cabaret,” collaborated for the last time on this provocative musical. (Ebb died in 2004) They took the cake(walk), flipped it on its head and served up a loaded, multilayered slice of musical theater.

In fact, the show opens with a demurely dressed woman (Shalaye Camillo) carrying a cake box who walks to center stage and takes a seat. A proscenium lights up behind her and we find ourselves at a minstrel show — with a white Interlocutor who identifies himself as the master of these black boys, who, we’re told, will sing and dance for us. We’re immediately made uncomfortable, but Kander and Ebb’s music and lyrics and David Thompson’s book walk that tricky line between entertainment and terrible truth with powerful confidence.

Unlike an historic minstrel show, with its white (and often black) actors in blackface playing stock characters that caricature black folks, this cast of minstrels is entirely black. It proceeds to caricature the white folks, from the women who initially accused the boys to the politicians, police and lawyers who victimized them. The show takes the racial stereotypes of minstrelsy and puts them at the mercy of a true tale of racial prejudice.

This subversive device is as brilliant as it is disturbing, affording us a rich menu of gospel, blues, ragtime, jazz and tap, and paying homage to the song, dance and narrative foundations upon which musical theater is built.

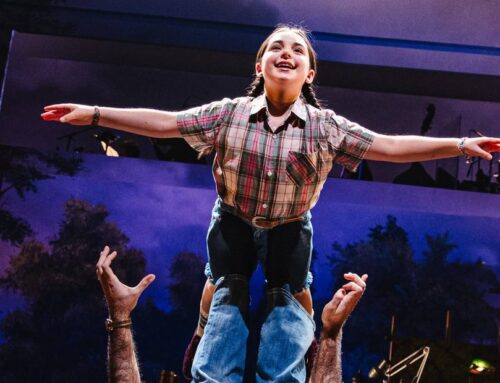

This cast is more than up to it. The actors who play the nine Scottsboro Boys (many play several other roles) register as separate, vivid personalities on stage, each with a heartbreaking story to tell.

The narrative focuses especially on one Haywood Patterson, played by De’Lon Grant. Tall, handsome, possessed of a rich voice and extraordinary dramatic presence, Grant demands our attention as the heart of the show. Watching him “free as air” singing with the rest of the cast on that train “Commencing in Chattanooga,” when we know all their hopes will be derailed, is crushing.

Maurice Emmanuel Parent brings his dazzle to this show’s conception of Bones, one of a pair of stock minstrel characters, in a variety of stinging guises. As his partner Tambo, Brandon G. Green is

equally effective in that and several other parts, notably as the “Jew lawyer” Samuel Leibowitz who attempts to overturn Haywood’s conviction while bearing a load of antisemitic prejudice himself. As the Interlocutor, Russell Garrett manages this inverted circus with great dignity and the subtle irony of a ringmaster who knows the show is rigged in the right direction.

That direction takes its cue from Elliot Norton Prize-winner Paul Daigneault, SpeakEasy’s artistic director. Though the original Broadway direction and choreography was by Susan Stroman, here it is Daigneault’s nuanced vision and Ilyse Robbins’ vibrant choreography which guide this work through its turbulent tone, swinging from entertaining to devastating.

Case in point: an upbeat tap dance number in which the Scottsboro Boys tap out the gyrations of someone sizzling in the electric chair. Later, a beautiful ballad sung by the boys in multipart harmony, like a hymn about those lovely “southern Alabama days,” finds its sweet melody suddenly wrapping itself around lyrics recalling “daddy hanging” from a tree and “crosses burning” in the sky. The effect is bruising –and enraging.

The musical accumulates considerable power, clear-eyed and unflinching as it draws to a close. The ending is as simple as the beginning. It concludes not with a song but with a ringing act of civil disobedience that continues to echo long after that train left the station.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.