Shakespeare said “All the world’s a stage” and that is literally true of the world as William Makepeace Thackeray saw it in VANITY FAIR here adapted by Kate Hamill now gloriously arrayed onstage at Central Square Theater: VANITY FAIR, AN (IM-) MORALITY PLAY. This production presented by Underground Railway Theater with a superb ensemble gives us Thackeray’s sprawling, serialized novel as the satirical/instructional/theatrical entertainment the author intended it to be. Director David R. Gammons brilliant set design embodies the novel’s framing tale–a puppet show dramatizing the tough lessons learned in a superficial society driven by money and power and the pursuit of “Vanity Fair,” the name of a stop on the King’s highway which Thackeray referenced in “Pilgrim’s Progress.”

Thackeray’s VANITY FAIR was subtitled a “Novel without a Hero,” and charts the progress and a reckoning for two “heroines” who are less than heroic but deeply human, and whose fortunes rise and fall on the vagaries of fickle society. This adaptation is certainly relevant in 2020 when the roles of women remain systemically encumbered, and are currently being re-evaluated through an ever “sharper” societal lens. This adaptation looks through that lens at two women and the men in their world, and they are all seen as equally flawed, but it’s the women’s stories which hold center stage. The cast also has equal access to these parts, sometimes playing against gender in multiple roles.

Becky Sharp, played by Josephine Moshiri Elwood, is a wily, young socially disadvantaged girl of questionable aspirations and bohemian origins: her father was an artist and her late mother an opera dancer who spoke French. Motherless, Becky must find a mate by hook or by crook, or both, as she makes her way up society’s slippery slope, first gaining a foothold as a governess in the creepy “Crawley” household (The cast shrieks in unison every time the word “governess” is spoken.) but her final destination involves being presented to the King. The vivacious Moshiri Elwood demonstrates Becky’s complexity as a flawed but sympathetic character, even in her worst moments.

Miss Sharp’s counterpart in this allegory is the docile, pleasing good girl, the wealthy Amelia Sedley, played with dignity and gentleness by the elegant Malikah McHerrin-Cobb. With eyes only for the good in people, especially her easily-led beau, the wealthy but wishy-washy George Osborne, Amelia is deeply loyal–at first a curse but later, a blessing. Likewise, Stewart Evan Smith shows us the true heart beneath George’s swagger and wobbly character.

Paul Melendy is inescapably funny in multiple roles including the ridiculously arch Headmistress Pinkerton, and surprisingly moving as the long-suffering Dobbin, George’s best friend who pines for Amelia. David Keohane shows terrific range as Becky’s dashing suitor Rawdon Crawley and Amelia’s proper fool of a father Mr. Sedley. Evan Turissini is excellent in multiple roles from Amelia’s doltish brother Joss to George’s hard-hearted father Mr. Osbourne .

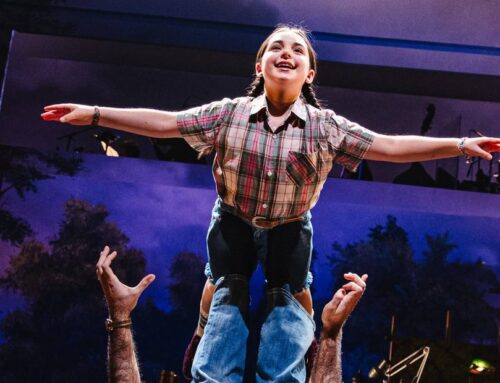

Presiding over all, is Debra Wise in a marvelous performance, pulling the strings as puppet master, manager, narrator, emcee who’s also engaged in the action: Wise does a bang up job as gaseous old Aunt Matilda Crawley seated on various thrones and holding the purse strings of the Crawley family’s future fortunes. Wise nimbly sets the tone, delivering her lines with a wink and a grin, and holding a copy of Thackeray’s novel lest there be any doubt about who’s really giving the cues.

All of which brings me back to the ingenious set and the way the staging facilitated the consolidation of the scope of Thackeray’s novel. Upon entering the space, there’s a series of small raised stages, set side by side across the width of the theater’s black box. Each actor pops in and out from behind the curtain of their individual little set, their wigs, costume changes, and props clearly visible as they duck in and out to perform. All at once, the arrangement suggests not only the novel’s puppet show framing device, but also the serial episodic entertainment that was the original, the parallel struggles among different characters, side by side in society high and low, as well as the perspective this arrangement allows the audience looking on from the outside in stadium seating –and the insight that distancing view affords.

The floor below these small stages, is littered with the subterranean detritus of material wants, acquired then discarded, along with an occasional body. I thought of the wreckage of all the preceding entanglements and reversals, as the manager cracked wise before the show ended and she delivered this final observation: “We want what we want and we can’t stop and we keep on wanting.” If that isn’t an epitaph for these bloated, hypocritical times, I don’t know what is.

DON’T MISS “VANITY FAIR, AN (IM-) MORALITY PLAY” at Central Square Theater through February 23!

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.