“APPROPRIATE” is a ghost story that has “appropriated” the familiar tropes of familial dysfunction and reveals some very “inappropriate” secrets that crack open a white southern family as they “unpack” the dark contents of their estate after dad has died. It’s an adventurous season opener for SpeakEasy Stage Company, written by hot young Obie Award-winning playwright Branden Jacobs-Jenkins who has given us a tale that subsumes race into the larger issues of identity that plague all families, black and white, in these still struggling to be United States.

ACT I of this Boston premiere is called “Book of Revelation” and opens in blackness at midnight in Arkansas, with the sound of what I thought were rabid crickets, but turned out to be cicadas finally mating in the penultimate moments of their 13 year lifespans. Indeed, some noise is about to be made and realizations birthed as a prodigal son stumbles home in the dark through the window of the dilapidated manse and former slave plantation where he was raised. Alex Pollock gives another tour de force performance as Franz, a screwed up soul seeking redemption, accompanied by his flower child girlfriend River, shrewdly played by Ashley Risteen who’s not as gentle or transparent as her name suggests.

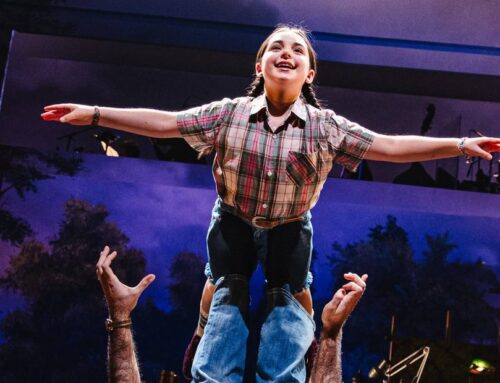

The house is a hoarder’s paradise; the detailed chaos arranged by Cristina Todesco suggests a place where secrets and spirits lurk. Soon Franz’s two other sibs, their families, and their “issues” arrive: no nonsense big city brother Bo (Bryan T. Donovan), his “just-so” wife Rachael (Tamara Hickey) and their two typical city kids Ainsley (Brendan O’Brien) and big sister 13 year-old Cassidy (Katie Elinoff). Oldest sister Toni (Melinda Lopez) who’s kept the home fires burning, is there to greet her returning brothers with a flammable mixture of wicked humor, exhaustion, and growing resentment. Her sullen teenage son Rhys (Eliott Purcell) is perfect as a young man torn and troubled by his parents divorce.

Act I is a tinder box of gothic irritation, sibling rivalry, and revenge, fueled by drugs, alcohol, accusations of sexual deviance, mental illness, legal wrangling, and anti-semitism, which is finally set ablaze by the discovery of an old photo album of gruesome images of mutilated slaves among dear old dad’s belongings. Not one but two graveyards molder just outside. The premise, the action, and performances– uniformly excellent, held me captive.

Act II called “Book of Genesis” attempts to wring a rebirth from the ashes of guilt and anger, and plays out as a melodrama of venting, screaming, fighting, questioning, and healing with echoes of all the “misfit disaster people” of dysfunctional families appropriated from the pantheon of American dramatic literature, most of which is white, kind of a “Long Day’s Journey” by way of “Streetcar” to the “Buried” bodies beneath, from Eugene O’Neill to Tennessee Williams, and a little Tennessee Ernie Ford for comic relief. A clunkily choreographed physical fight erupts onstage which is when the heat went out of the drama for me.

Despite its thoughtfulness, fine acting, and solid direction by M.Bevin O’Gara, this play is overstuffed and under-focused. On top of all the dark secrets, there’s an overriding layer about ownership– of human beings, their stories, and who profits, along with sidebars on marital strife, appropriate familial intercourse, the raising of children, and how we pass on the truth. And what of the effect of technology on how we process that truth? At one point, Cassidy, phone in hand and remarkably unshocked by the cruel images she sees before her, wonders aloud if she’s supposed to be upset by these pictures, and also why she shouldn’t just text them out to her friends. These are all worthwhile questions that could be the subject of a second or third play, with deeper, more nuanced characters.

This play hasn’t figured out how to fully integrate its various concerns without diffusing its dramatic impact.The show raises many more questions than it answers, all revolving around what to believe about the patriarch, and one another. As such, this isn’t a play about race as much as it is a drama about identity, and recognizing what we hide from ourselves and each other. It also seems the playwright means to use America’s racist history and its relationship to slavery which took deeper root in the south, not only as a catalyst for unlocking the contradictions and pain in the individual lives of his characters, but also as a way to understand the dysfunction of the larger “American family.” And that’s a conversation that is more than appropriate; it’s crucial right now.

See APPROPRIATE at SpeakEasy Stage Company through October 10– and let me know what you think!

[…] Joyce Kulhawik reviews APPROPRIATE […]

[…] you will. (Photographic images are pivotal to another of Jacobs-Jenkins plays seen here recently, APPROPRIATE). This evidence leads to the abrupt presentation of horrifying crimes documented in their future […]

[…] Like Sugar,” “How I Learned What I Learned,” “The Convert,” “appropriate,” “Saturday Night, Sunday Morning,” and “The Launch Prize,” to the […]